Brief History of African Investing

You Can’t Really Know Where You Are Going Until You Know Where You Have Been.- Maya Angelou

In the previous post, we explored the opportunities and challenges within Africa’s stock markets, making the case that, despite risks, equities are among the best wealth-building tools for African investors. In this part, I want to push the message further: investing in African stock markets isn't a modern phenomenon—it's a continuation of initiatives with deep historical roots.

“When you buy a stock, you become a part-owner of an enterprise.”

Warren Buffett

Stock market investing isn’t a foreign concept in Africa. Historically, African nations have embraced similar investment initiatives to stimulate economic growth and promote wealth-building. These initiatives might not involve stock exchanges in the modern sense, but they demonstrate how African societies pooled resources, distributed wealth, and invested in economic ventures collectively—key principles that align with the concept of stock markets.

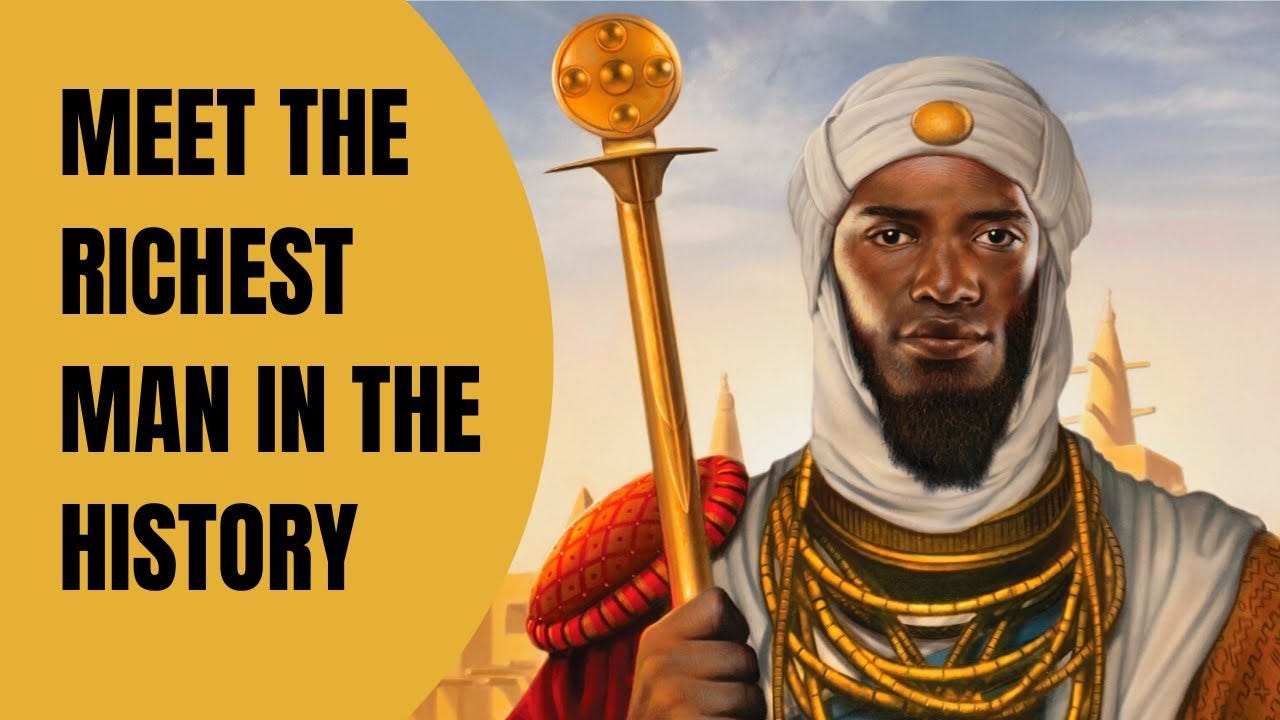

The Richest Man of All Time - Mansa Musa

The Mali Empire's legendary affluence was no accident; it resulted from meticulous management of the gold trade—a precursor to modern resource-based investments. The empire's economy thrived on the wealth generated from gold and salt, much like today's resource extraction companies fuel national economies.

Question to myself first and to you: Why can’t we go back to this?

Wealthy individuals and families within and outside the empire pooled resources for large-scale trading expeditions, much like investors today pool funds to invest in companies. They did this with the understanding of the risks involved—such as fluctuations in gold prices and the uncertainties of trans-Saharan trade routes. These risks mirror the volatility of modern-day stock markets.

During his famous pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324, the leader of the Mali Empire, Mansa Musa, distributed so much gold that he caused inflation in regions like Cairo, Medina, and Mecca. The sudden influx of gold devalued the metal, leading to price increases—a phenomenon similar to modern hyperinflation caused by an oversupply of currency.

In today’s context, Mansa Musa could be seen as a major market mover whose decisions would have the power to influence global market prices. If Mansa Musa were a modern-day investor, he would likely be a prominent figure in global financial markets, comparable to Warren Buffett. His actions would likely cause market fluctuations, much like announcements by influential investors or corporations today lead to stock market volatility.

West African Venture Capitalists

In precolonial West Africa, extensive trade networks existed between kingdoms like the Ashanti Empire, Benin Kingdom, and the Songhai Empire. These networks were the backbone of the trans-Saharan trade.

These networks functioned similarly to investment pools. Merchants would join together, pool their capital, and invest in trade expeditions or the production of goods. These associations were essential for managing risks and distributing wealth among members—much like shareholders in a company.

If these trade guilds existed today, they would likely resemble modern venture capital firms. These networks, which historically pooled resources for large-scale trading expeditions, would now invest in startups, infrastructure projects, and international trade ventures. They would function as organized entities that manage collective investments, providing capital to promising businesses and sharing the profits among members.

The Omani Empire

The Omani Empire controlled much of the Indian Ocean trade, dealing with commodities like ivory, spices, and slaves. Merchants in Zanzibar invested heavily in these goods, funding large trading fleets that would sail to the Arabian Peninsula, India, and even Southeast Asia. This long-distance trade required the pooling of capital and involved significant risks and rewards, much like stock market investments today.

Wealthy families or groups of investors would sponsor caravans or shipping expeditions, hoping for high returns on their investments. They would pool capital to finance expeditions, with the understanding that profits or losses from the journey would be distributed among the investors according to their share of the investment, similar to receiving dividends from stock investments. This concept would later evolve into Sukuk, often called Islamic bonds, which are financial certificates representing a proportionate interest in an underlying asset, investment, or partnership. This parallels stock market investing, where individuals invest in companies (expeditions) with the expectation of profit (returns).

The 16th Largest Stock Market in the World

The Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE), one of the oldest stock exchanges in the world, was founded in 1887 during the Witwatersrand Gold Rush. This wave of investment helped South Africa's economy boom and laid the foundation for the country's financial markets.

When comparing the JSE’s performance over the last century, it ranks globally as one of the top-performing stock markets. South African equities have consistently delivered long-term solid returns, outperforming several major markets, including France, Italy, and Japan. In fact, between 1900 and 2020, the JSE’s annualized real returns stood at approximately 6.4%, making it the 3rd best-performing stock market over the past 100 years.

How Africans Invest

Investing in Africa is not a recent phenomenon but a continuation of a rich tradition of collective economic activity. In Kenya, traditional saving schemes represent an impressive 7% of the country's GDP. These groups pool funds for savings and strategic investments that echo the mutual efforts of investment funds.

Similarly, West Africa's Susu’s and Tontines, South Africa's Stokvels, and North Africa's Jam'iyya are communal savings mechanisms that have long provided their members access to capital for personal and community growth. These traditional practices are marked by regular contributions that are rotated among members, allowing each participant a chance to invest in more significant ventures than they could individually.

These communal investment initiatives serve as a testament to the power of community-based financial strategies, mirroring the objectives of modern investment funds. They demonstrate the same principles of pooling resources and sharing risks and rewards fundamental to stock market investing.

These traditional models have evolved, with many transitioning into formal cooperatives and credit unions, reflecting the structured approach of contemporary finance. The essence of these systems—collective investment and mutual benefit—remains central to the ethos of African economic practices.

History Repeats Itself

For today's African investors, engaging in stock markets represents a natural progression from historical communal savings models, maintaining the spirit of shared economic prosperity while participating in a globalized financial environment. The aforementioned historical context underscores the notion that stock market investing in Africa is not a new concept but rather an ingrained practice reimagined and adapted to the current economic climate.

To better understand the current landscape and opportunities in African stock markets, check out